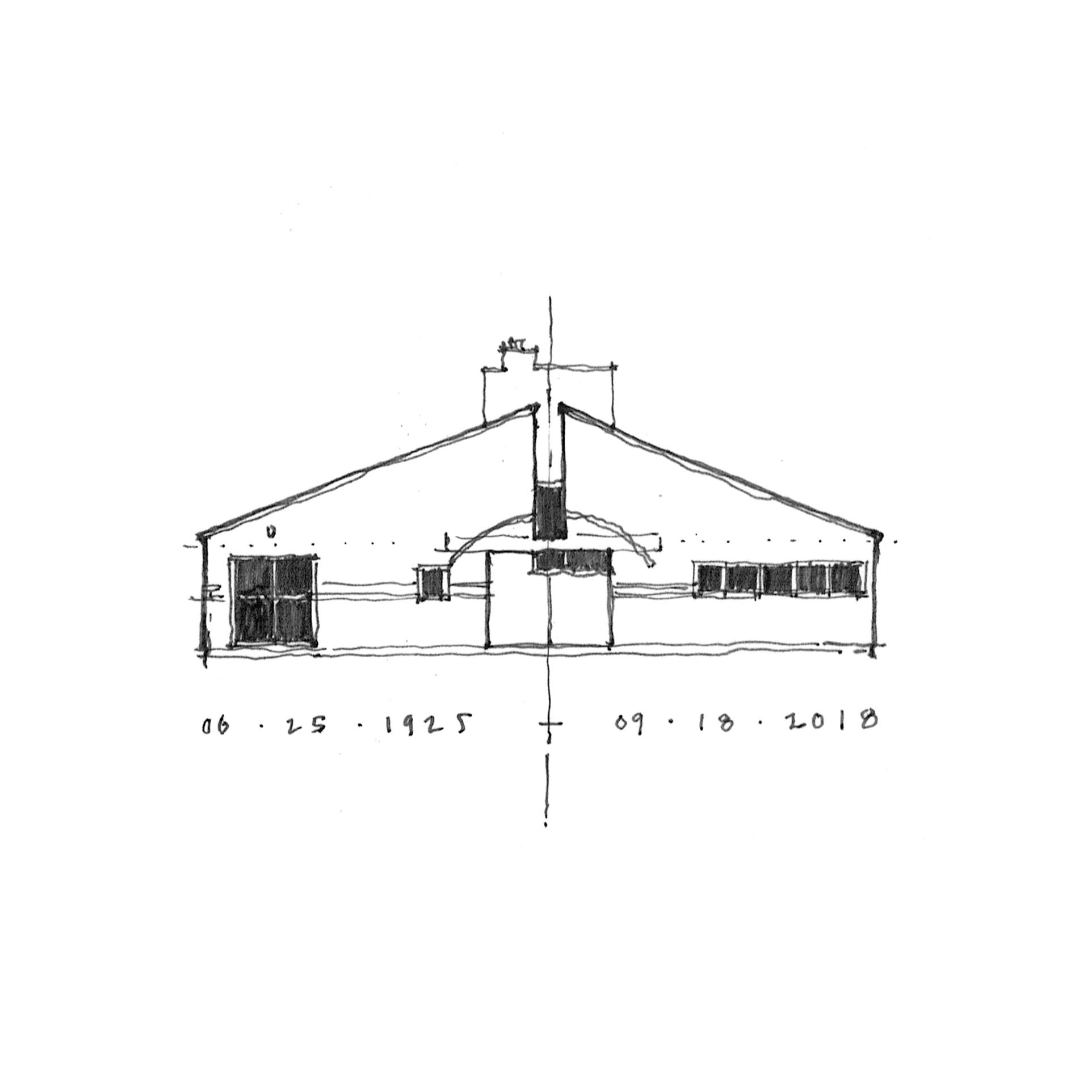

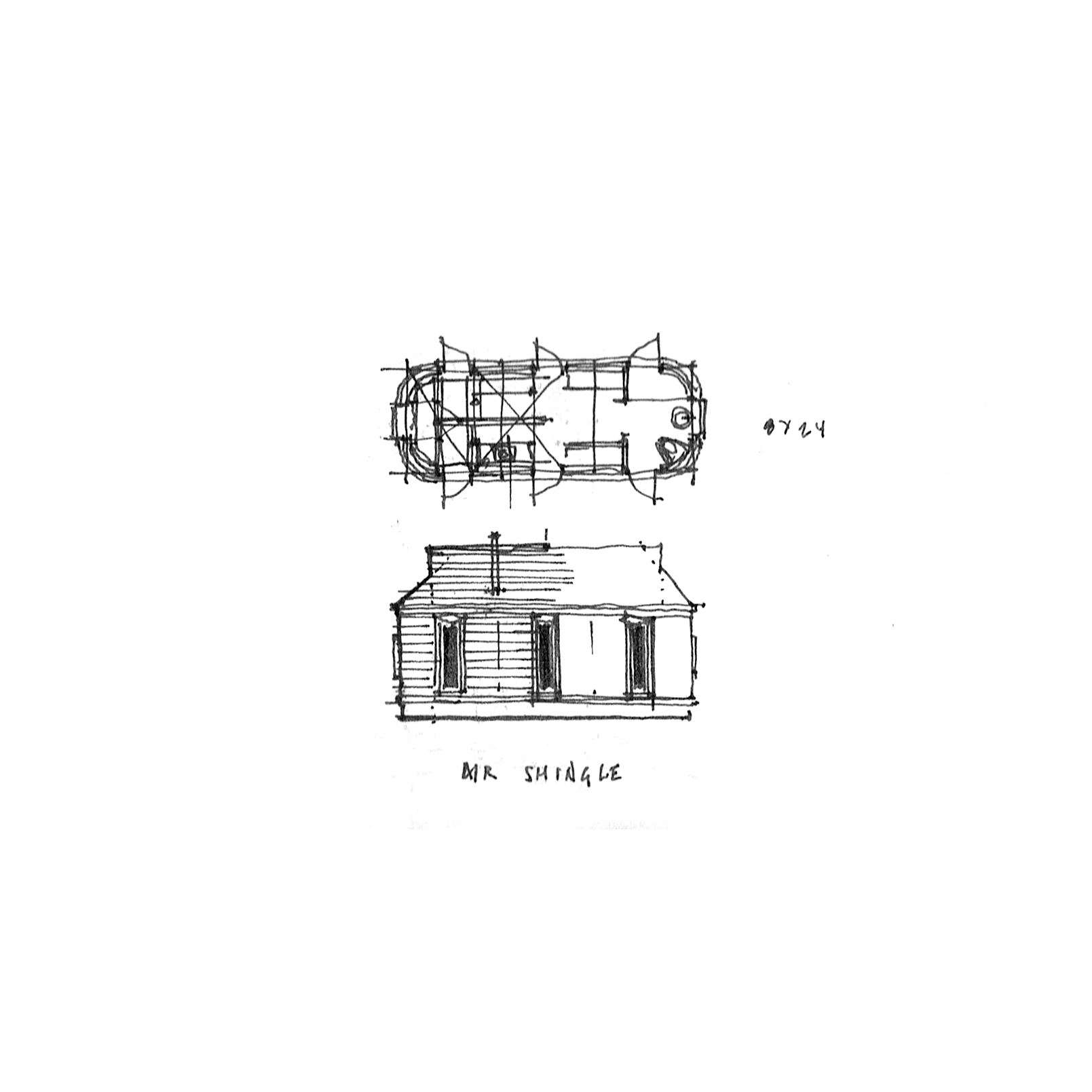

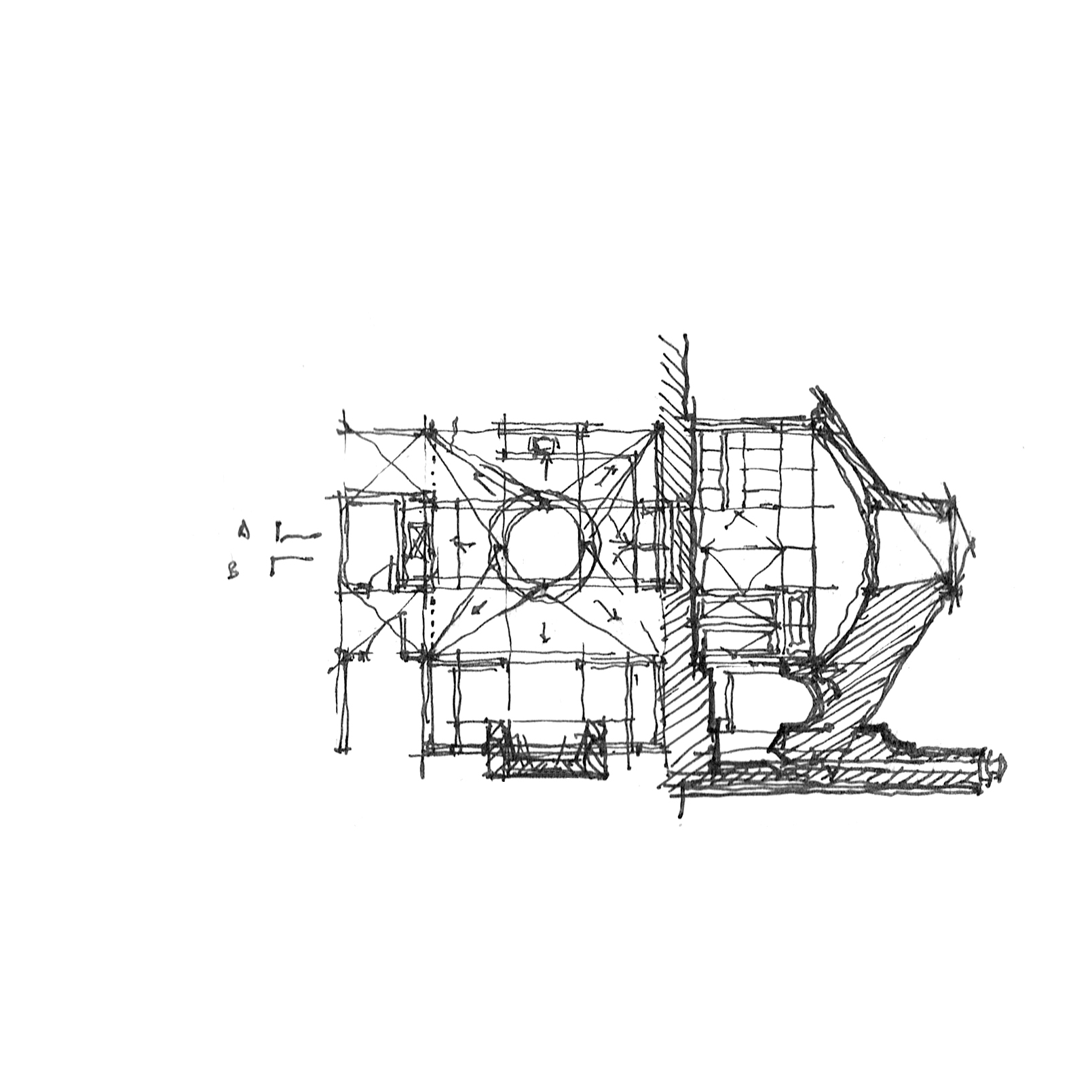

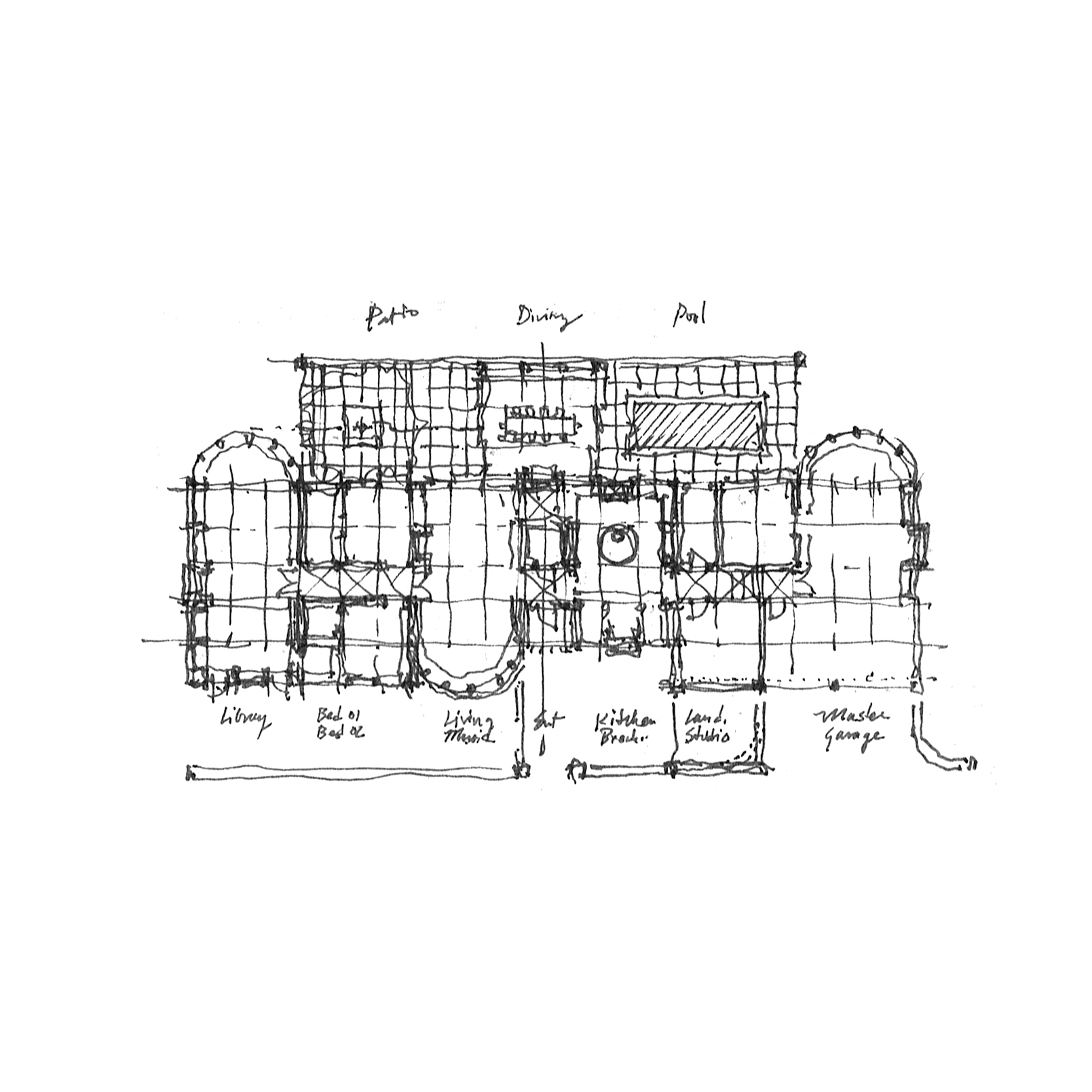

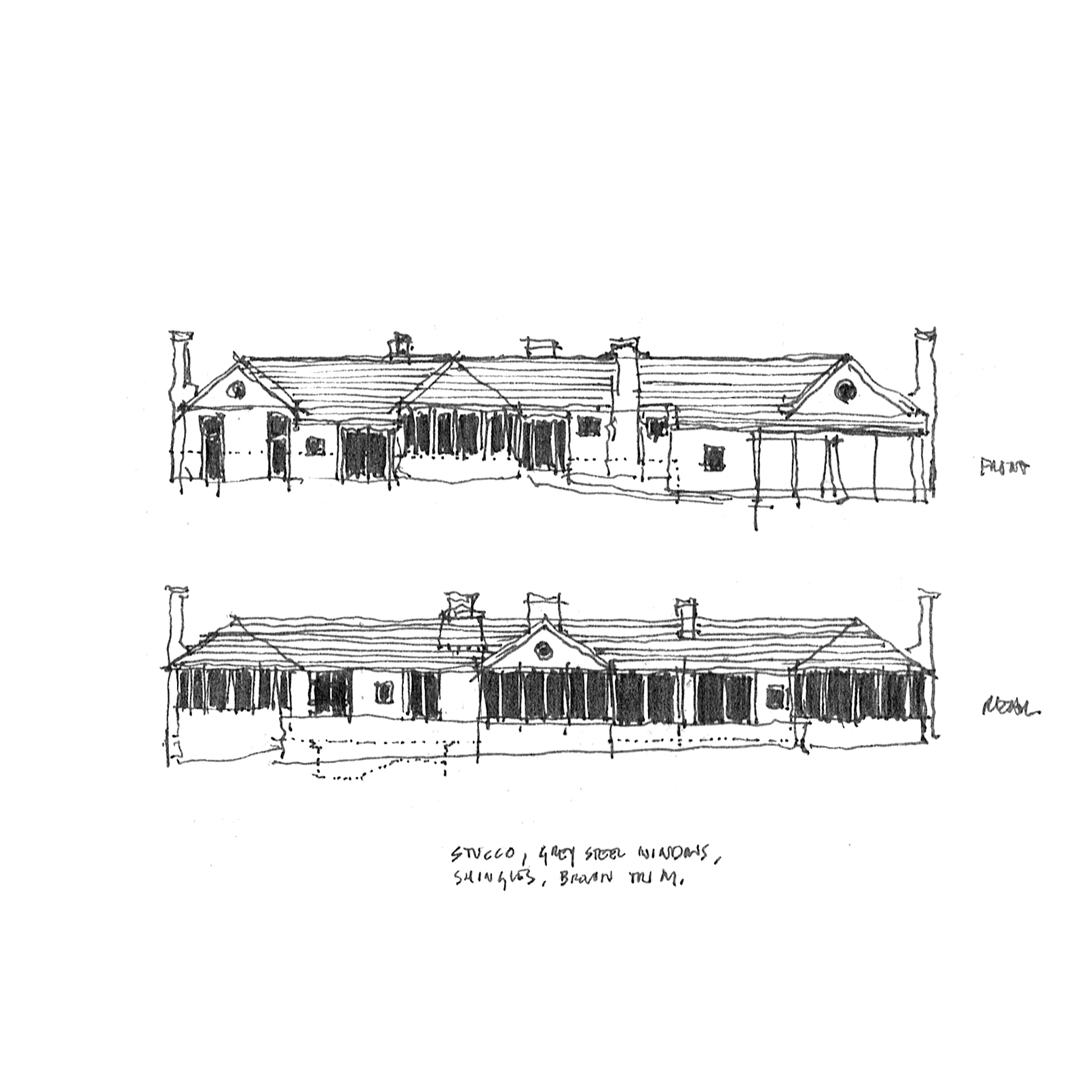

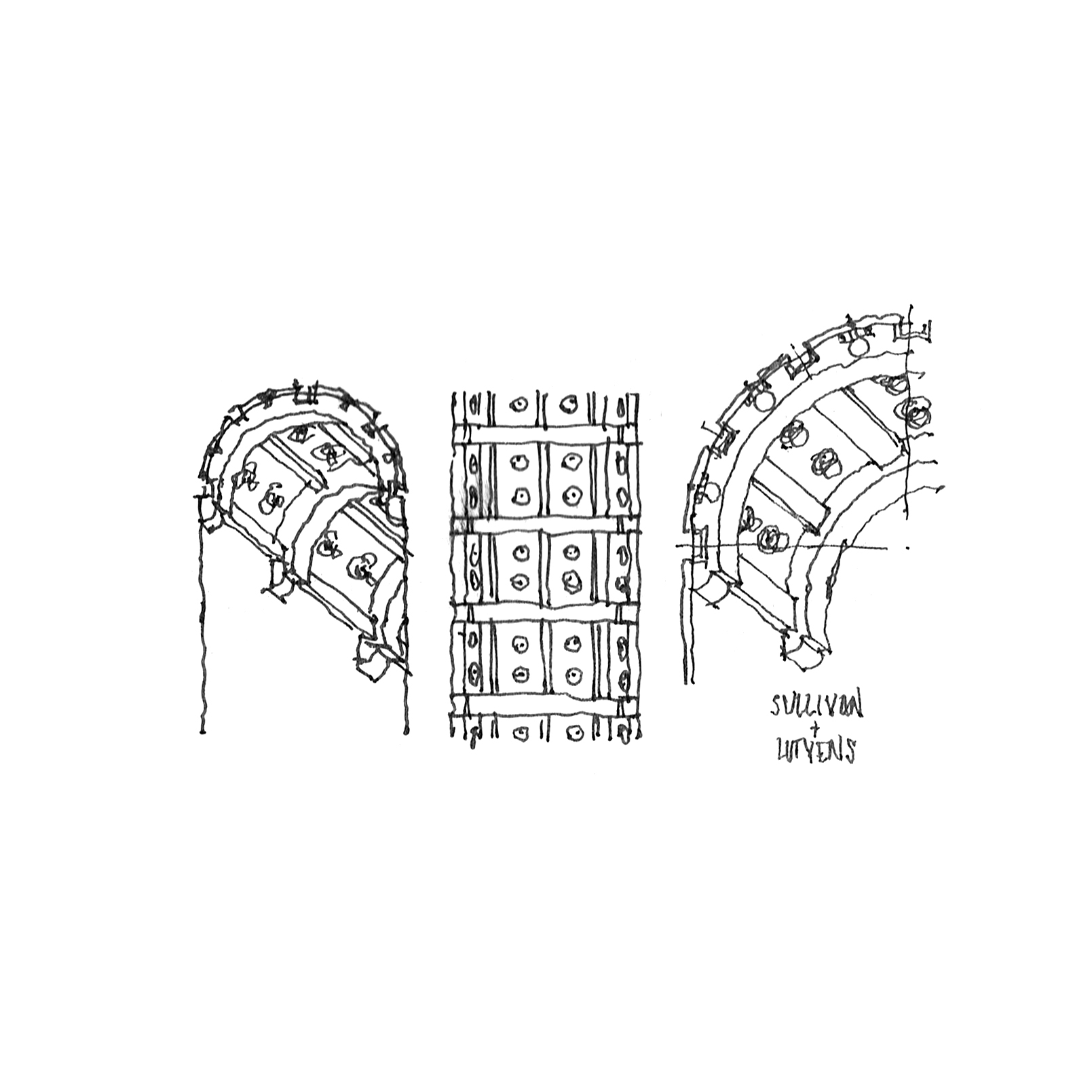

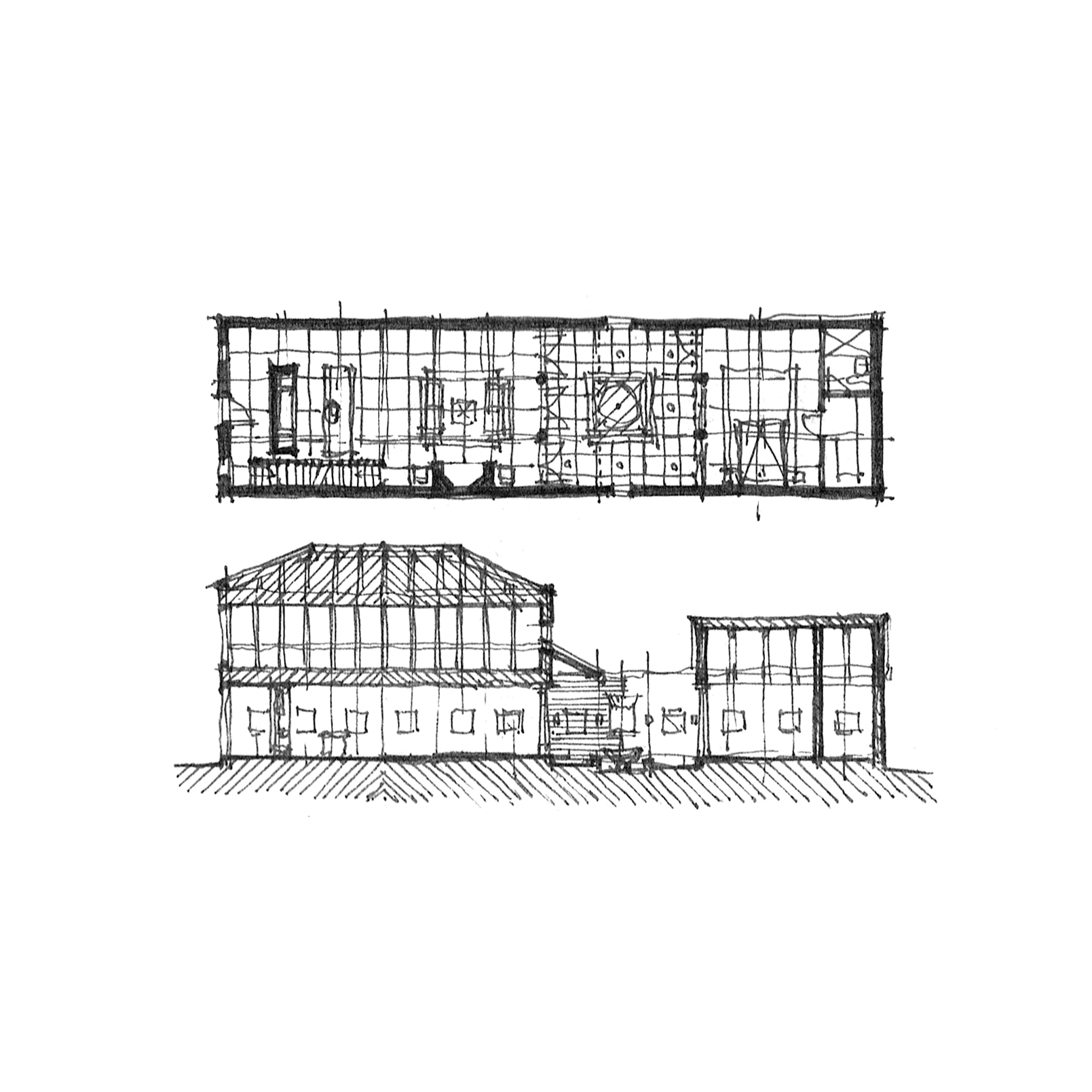

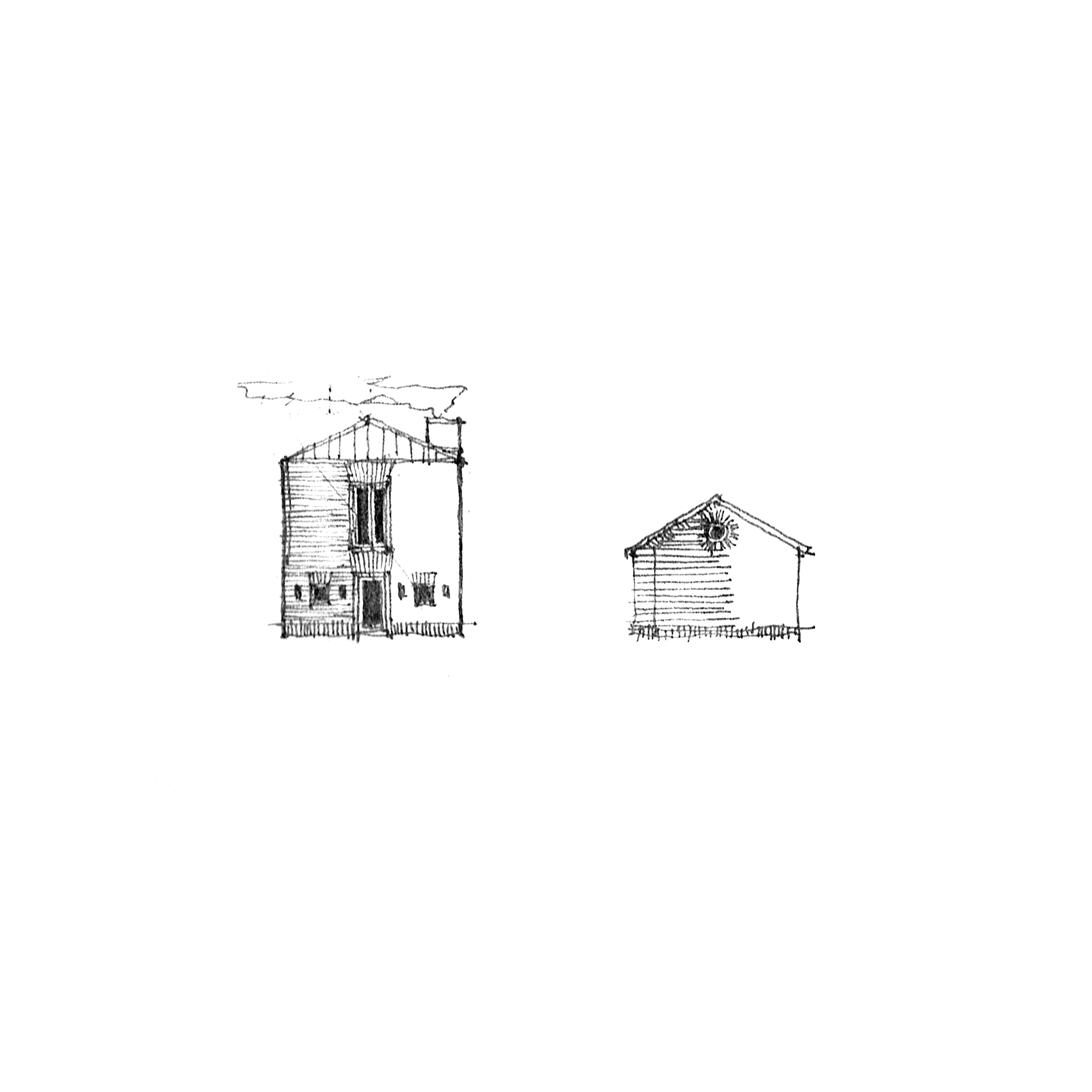

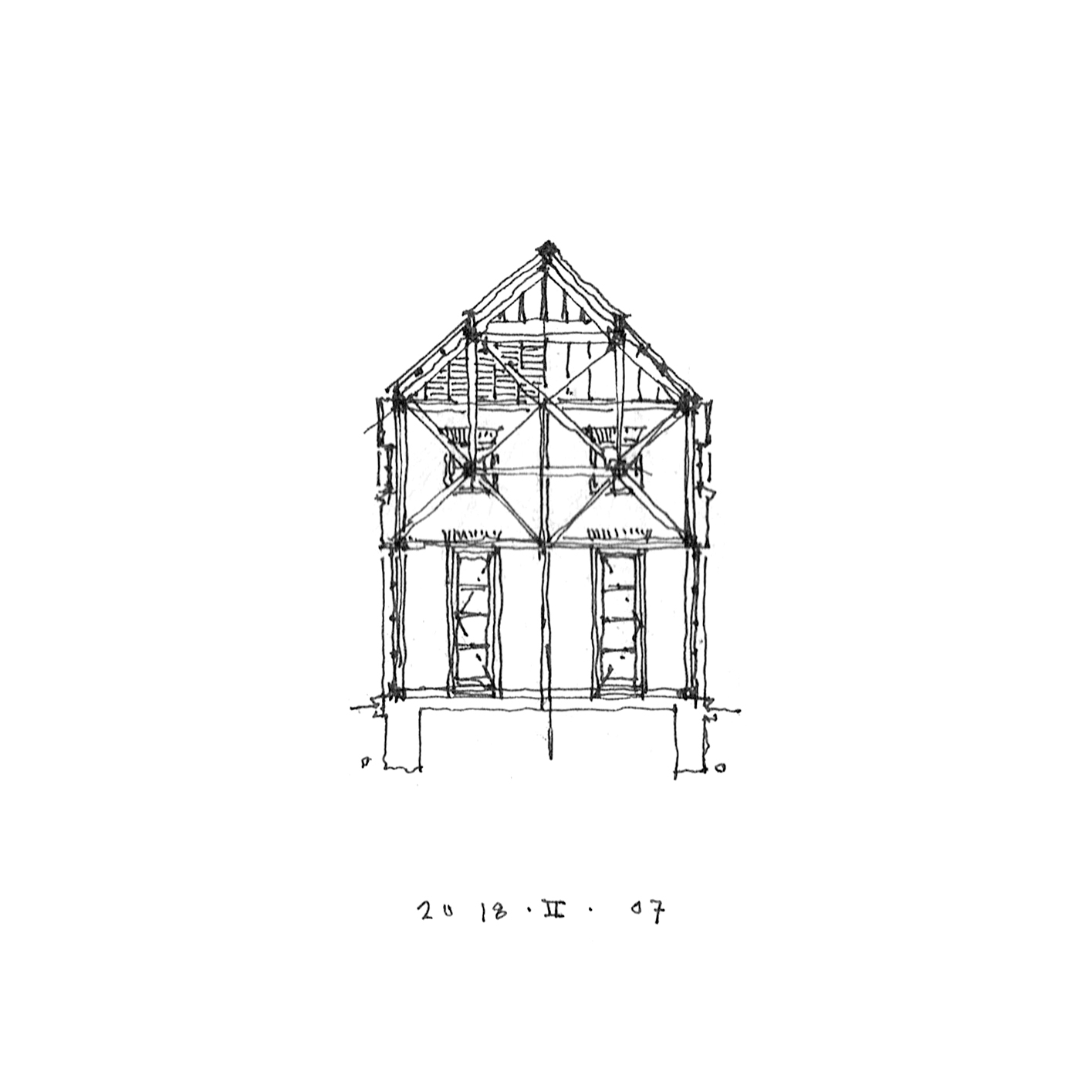

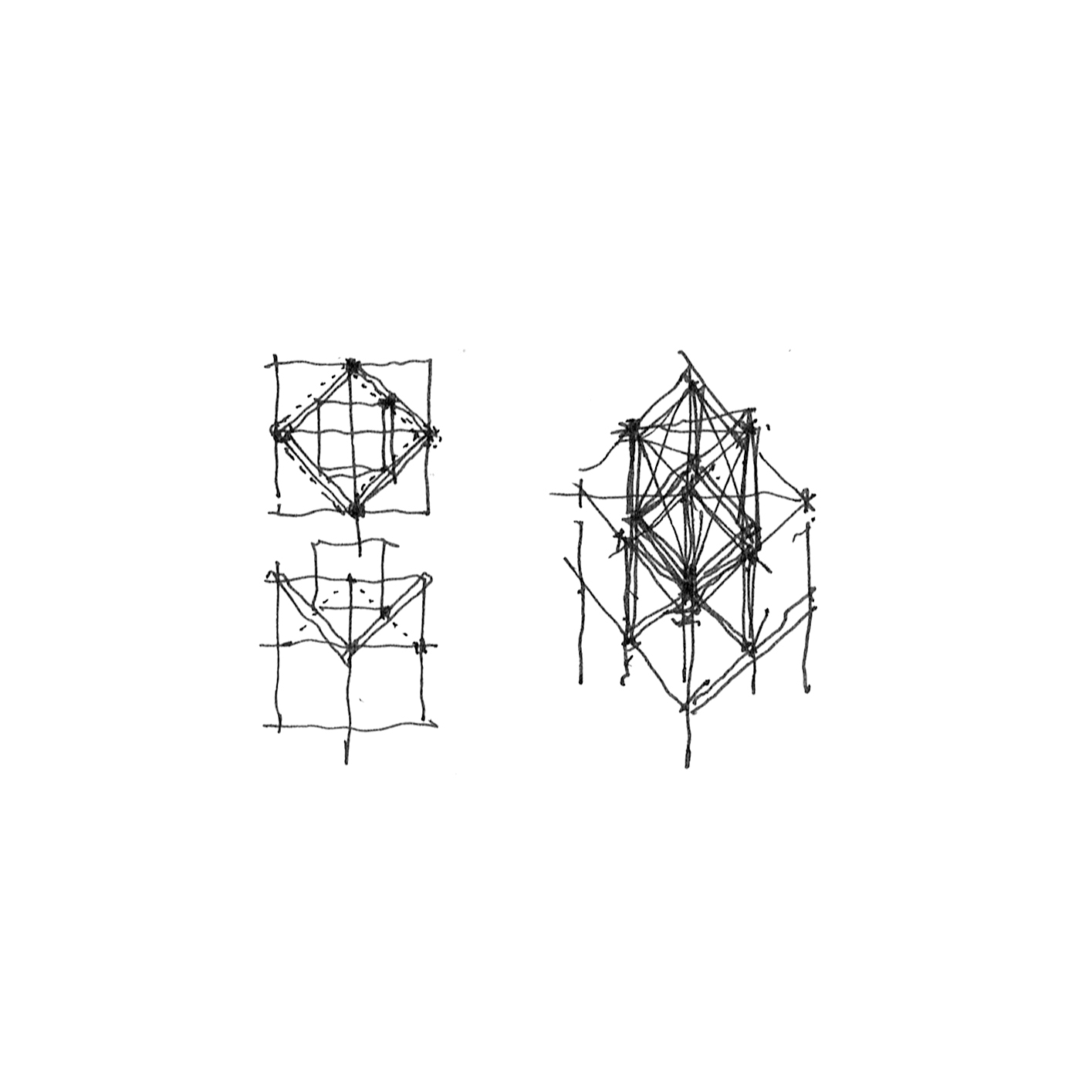

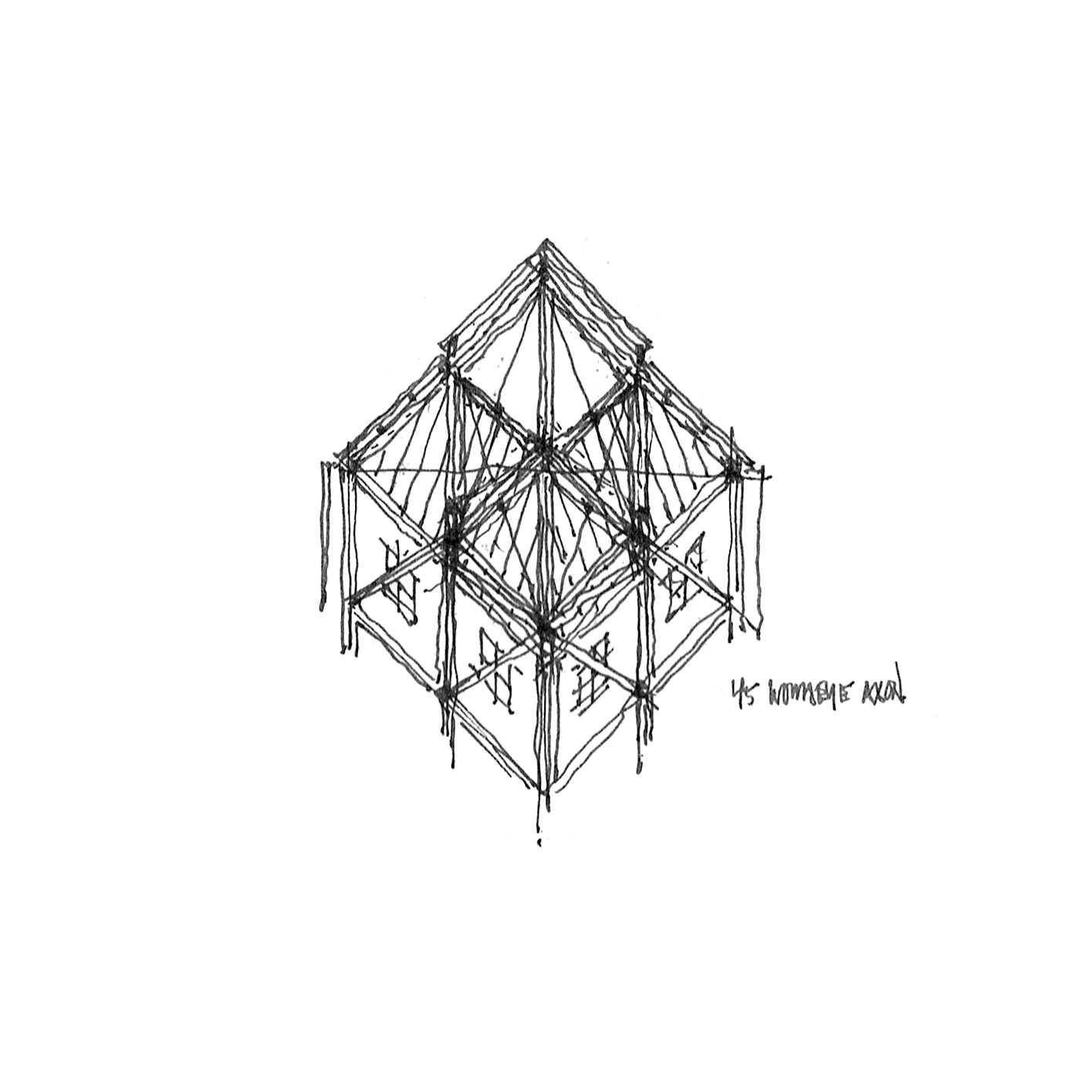

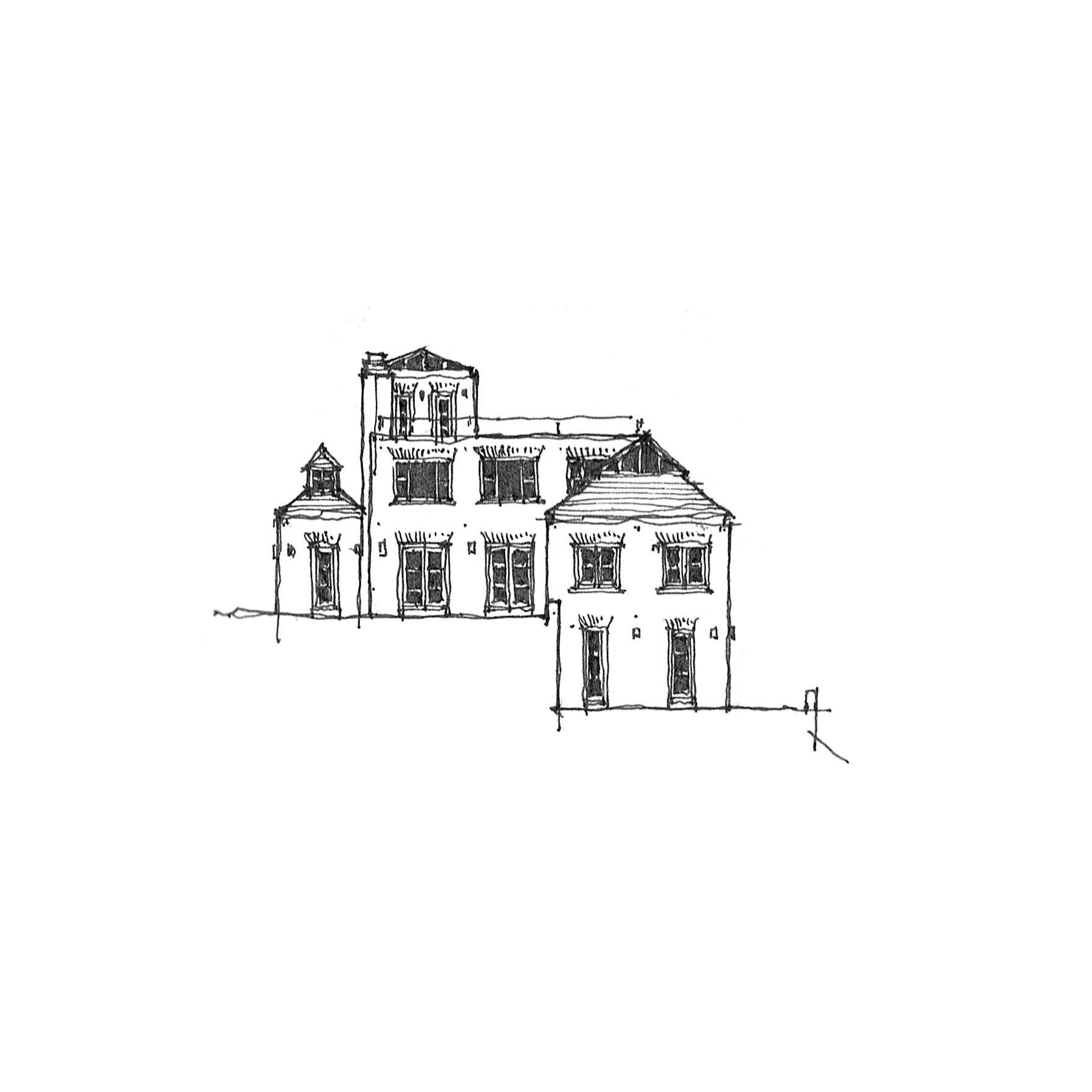

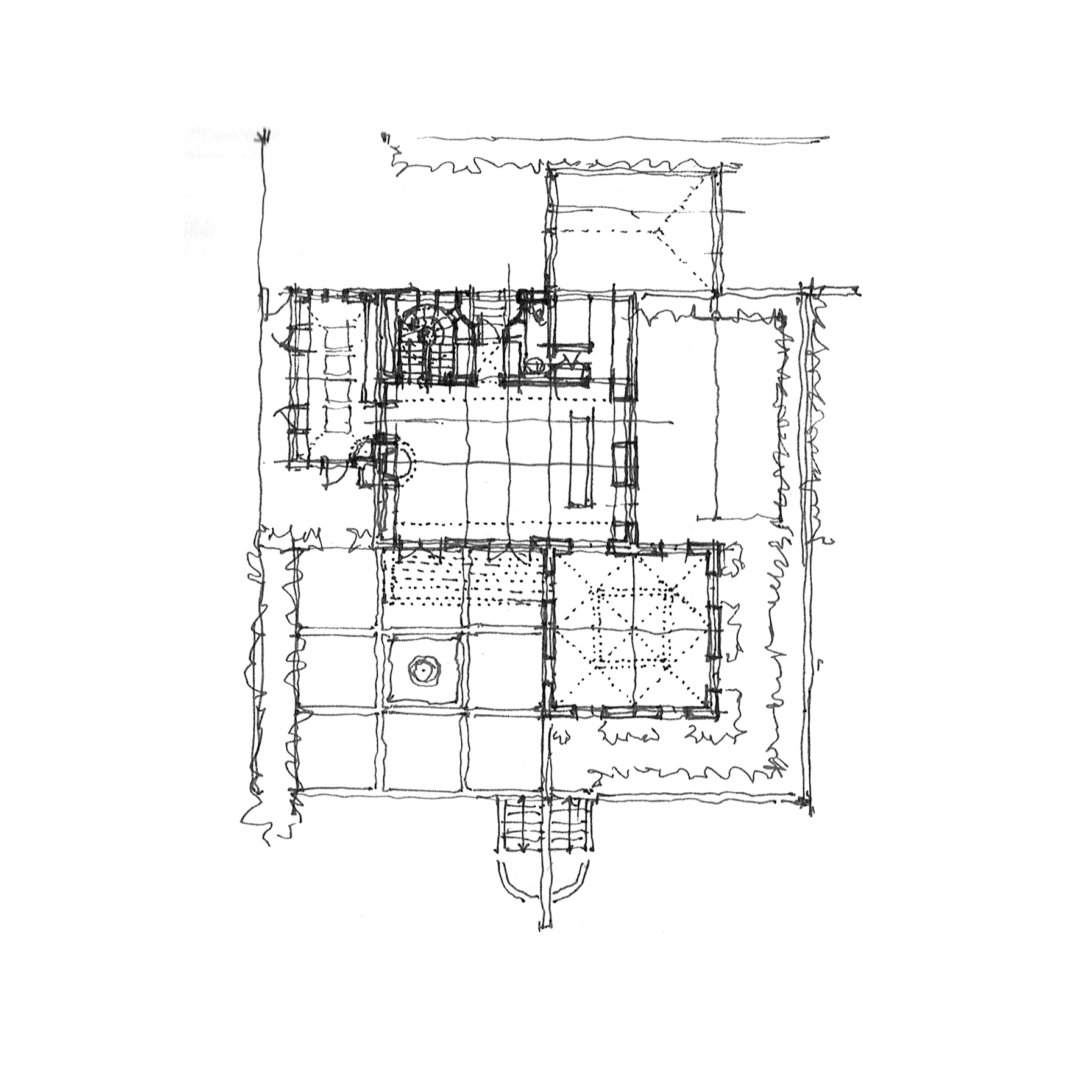

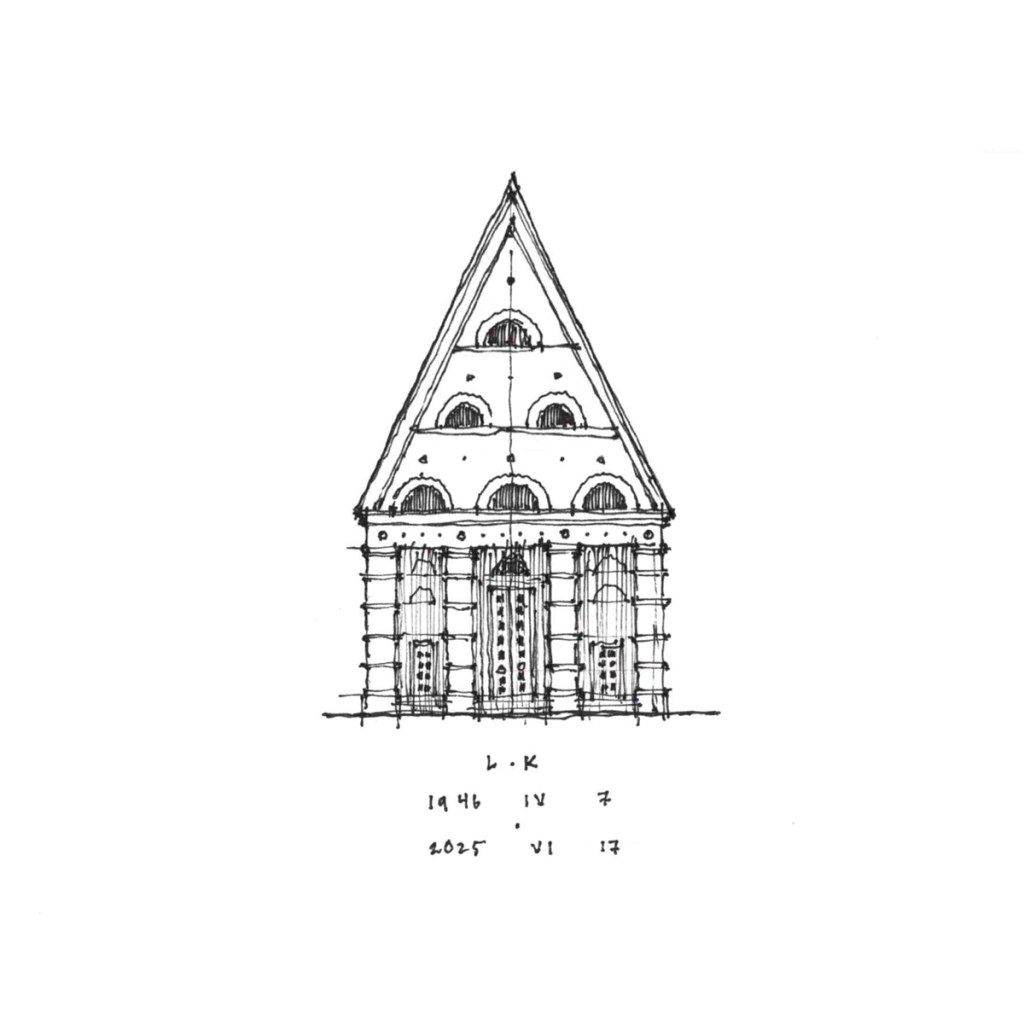

This is a hard one. Leon Krier was a stalwart polemicist, and though I have taken exceptions to his arguments, he has always remained a heavy influence on me. Especially in pioneering drawing as argument, a tactic this drawg has taken since day one. From urbanism to the simplest of follies, Leon carried arguments through his drawings. His built work may not have been numerous, but his impact will continue for generations through the work of his hands, pen, and paper.

We met only once, but remained in contact via email for years, him always attentive to my questions and requests; countering the sketches I would send him with a host of his own, often unpublished. Early on, he graciously agreed to my posting a few of those on this very site. Of all living influences on my work, none other has remained so constant, save my personal mentors and friends.

Merci, Leon.