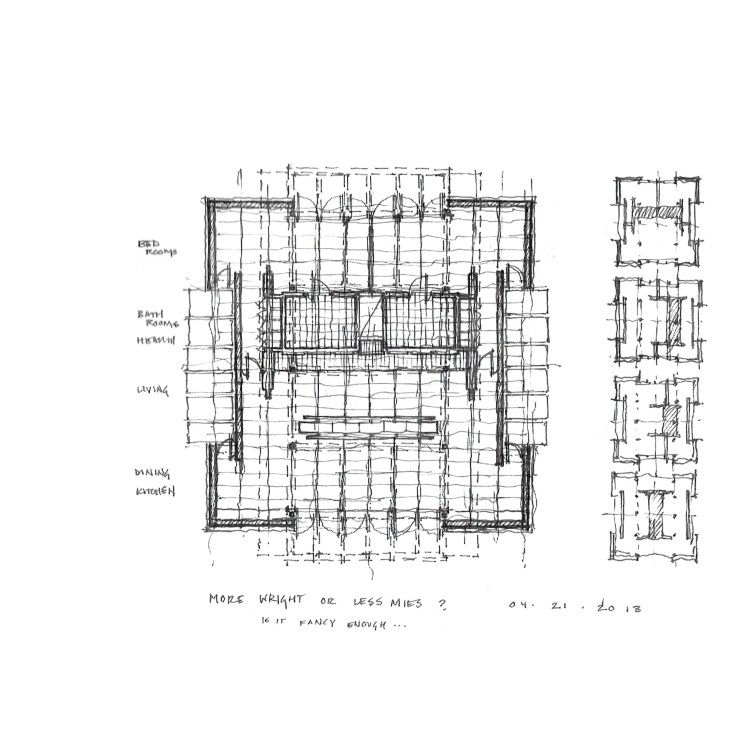

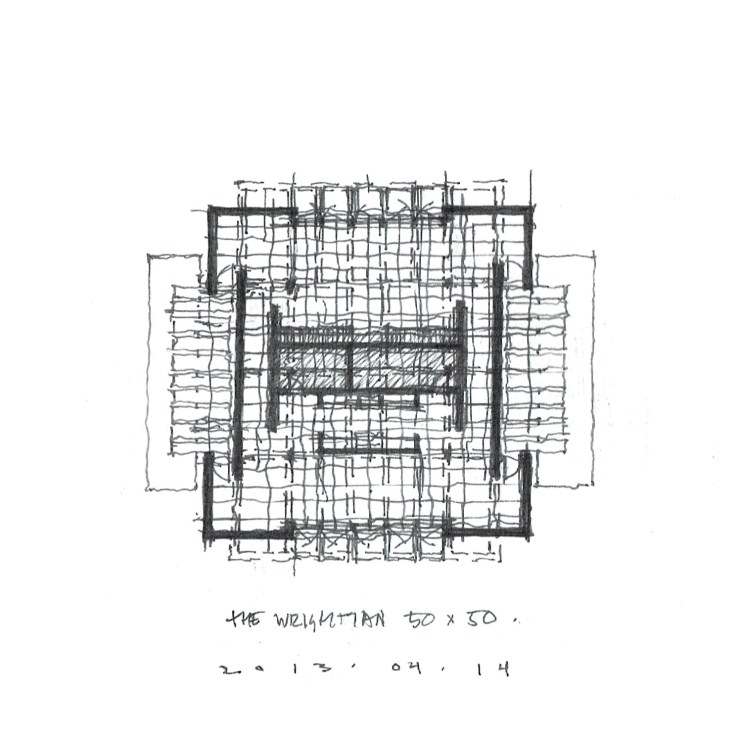

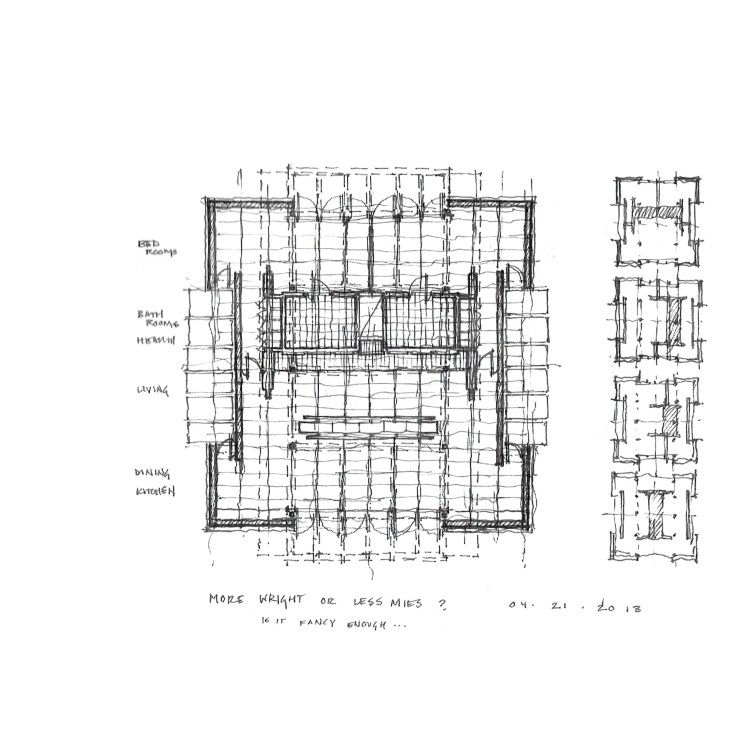

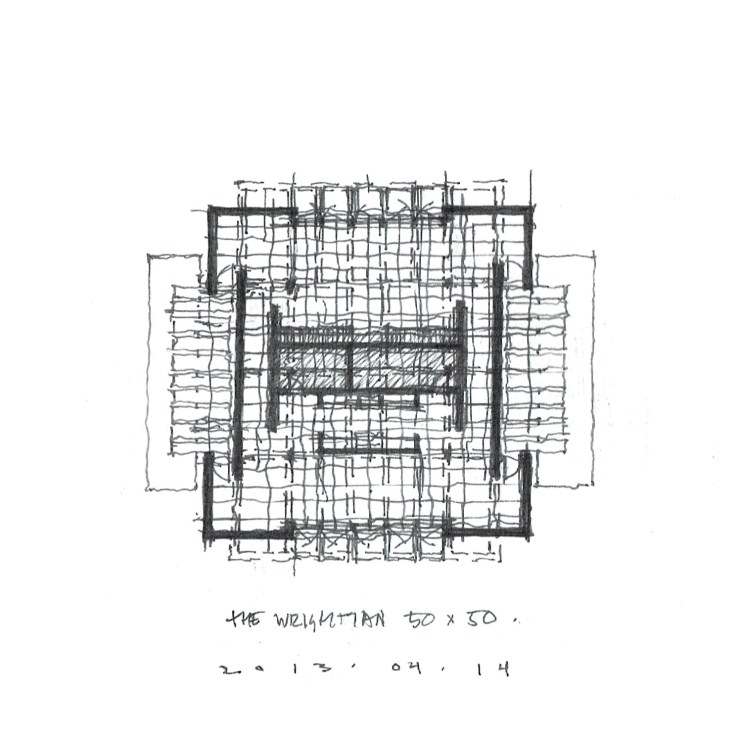

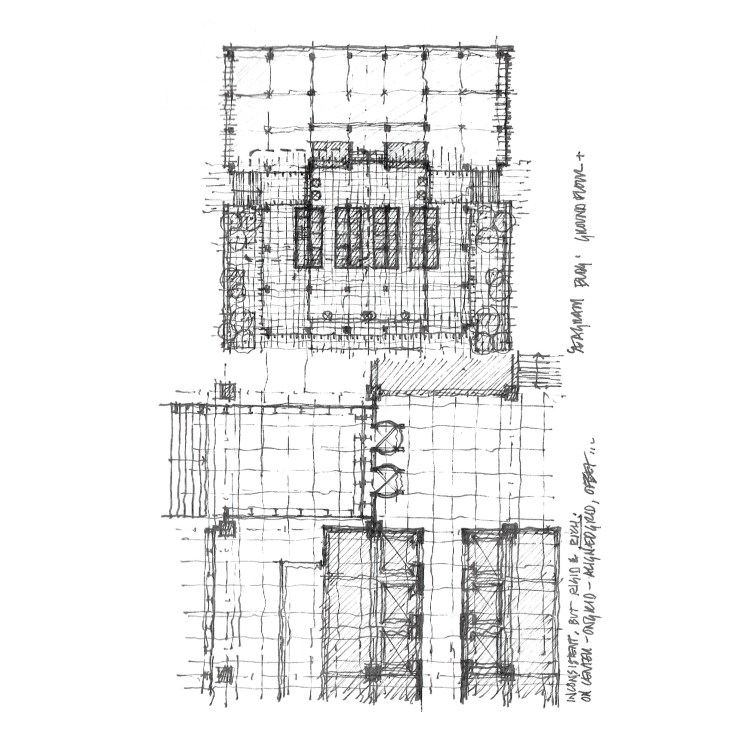

Yet another take on the theme, this time with a symmetrical wrapper, with studies on how the core might sit within the volume. The thought was to more directly synthesize Wright’s Usonian Houses with Mies’ 50X50 House. But more on those later.

Yet another take on the theme, this time with a symmetrical wrapper, with studies on how the core might sit within the volume. The thought was to more directly synthesize Wright’s Usonian Houses with Mies’ 50X50 House. But more on those later.

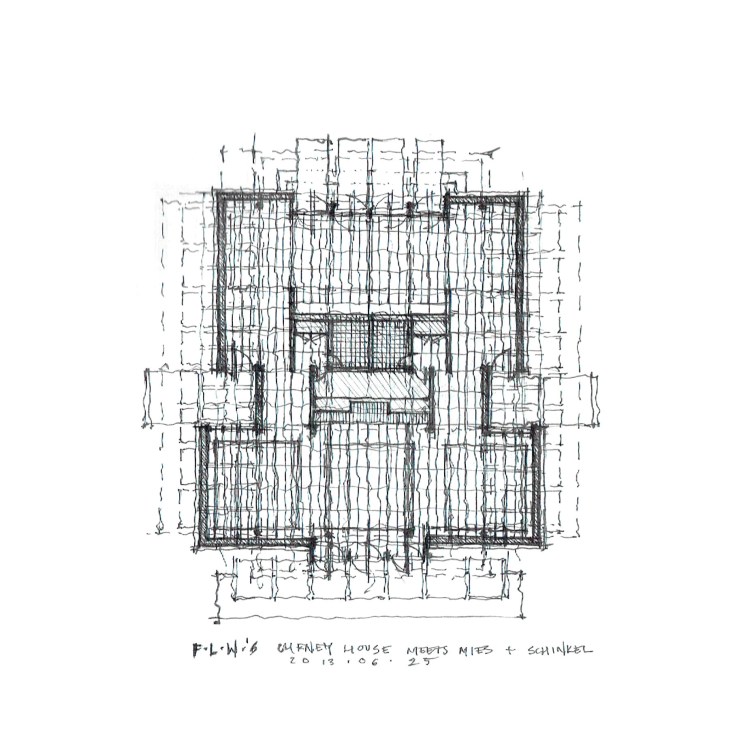

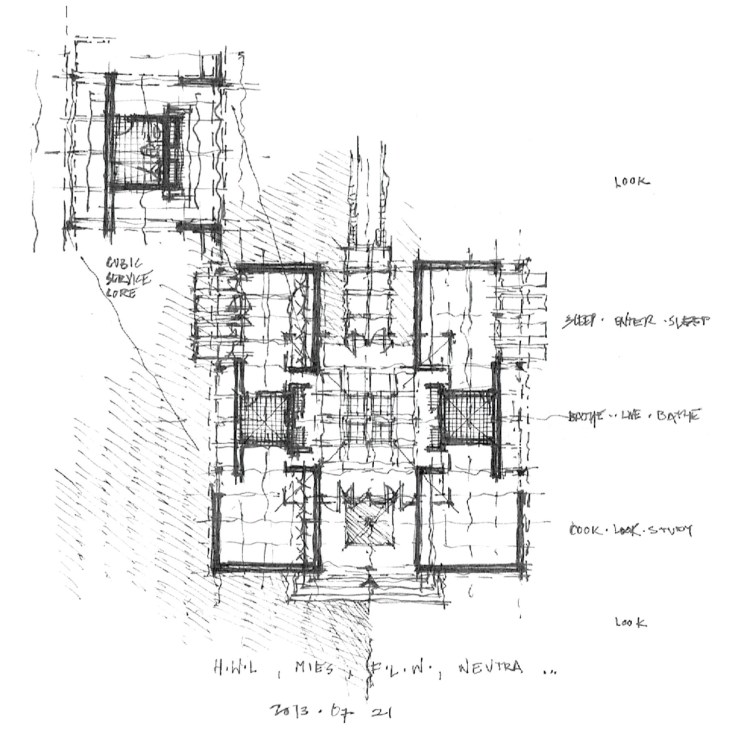

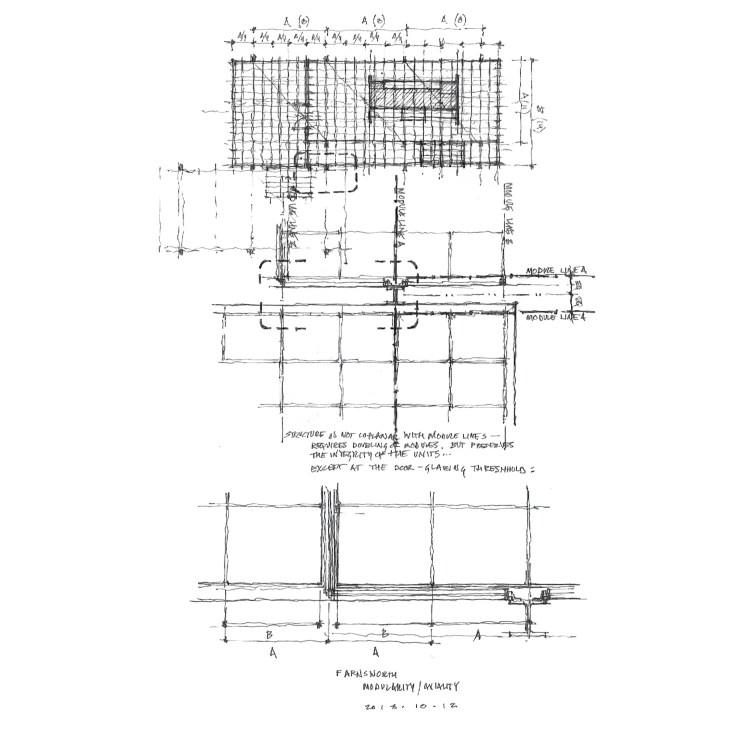

So I took the Cheney house plan and put it on Mies’ module, replaced the central hearth with a modified Farnsworth core just to see what happened. Iterations ensued, and even Schinkel reared his head.

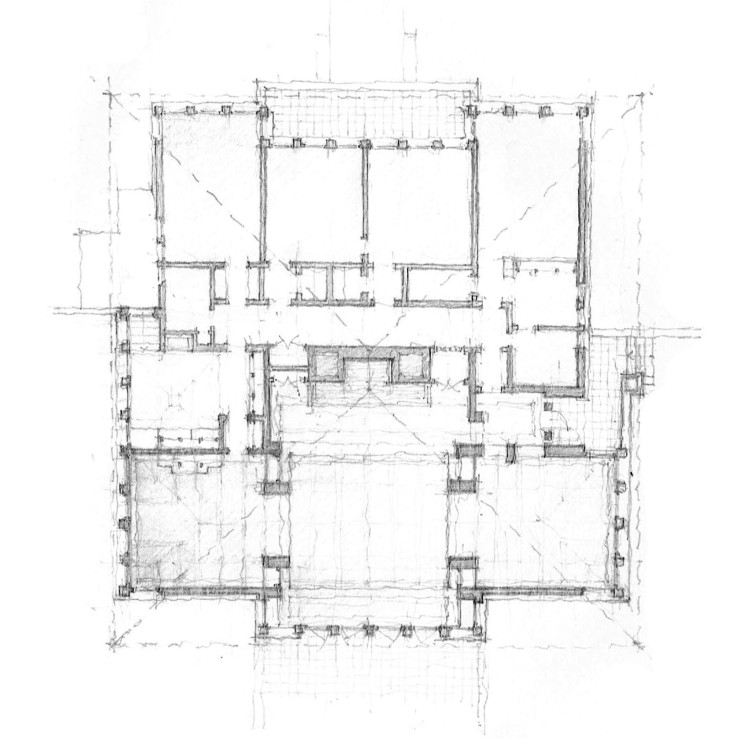

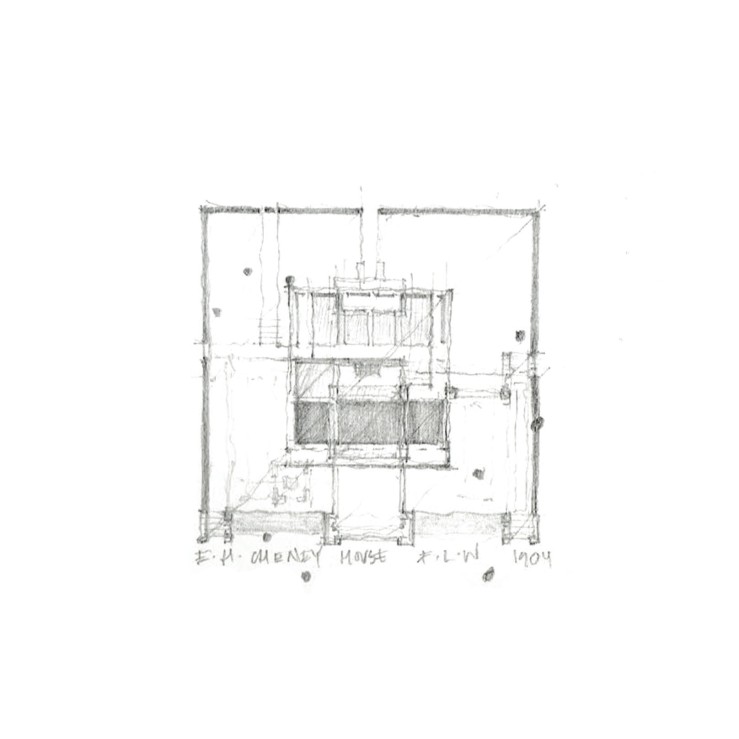

Keeping the Chicago theme, but moving a bit back in time, today I’ll feature some early Frank Lloyd Wright, particularly the Cheney House in nearby Oak Park. The plan is fascinating because it is an effectively square structure under a large hip roof, divided into two halves: the front is made up of three public rooms (nine square), while the back is broken into four bedrooms (four square), with servant spaces filling out the middle. The hearth is at the very center of the house, typical Wright. This basic parti (formal planimetric diagram) still fascinates me to this day – a simple form with a complex, yet brutally clear interior logic. The variations it inspired will follow over the coming days.

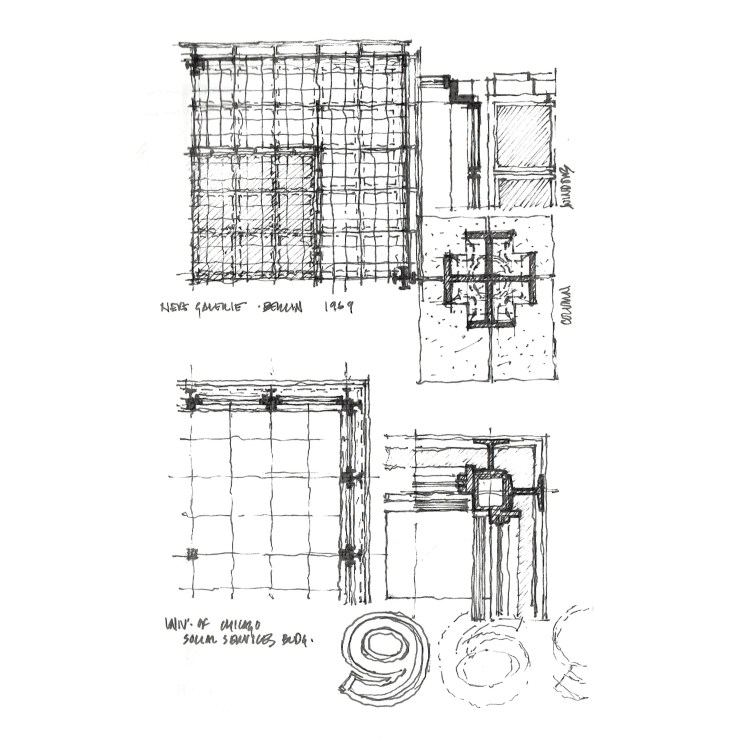

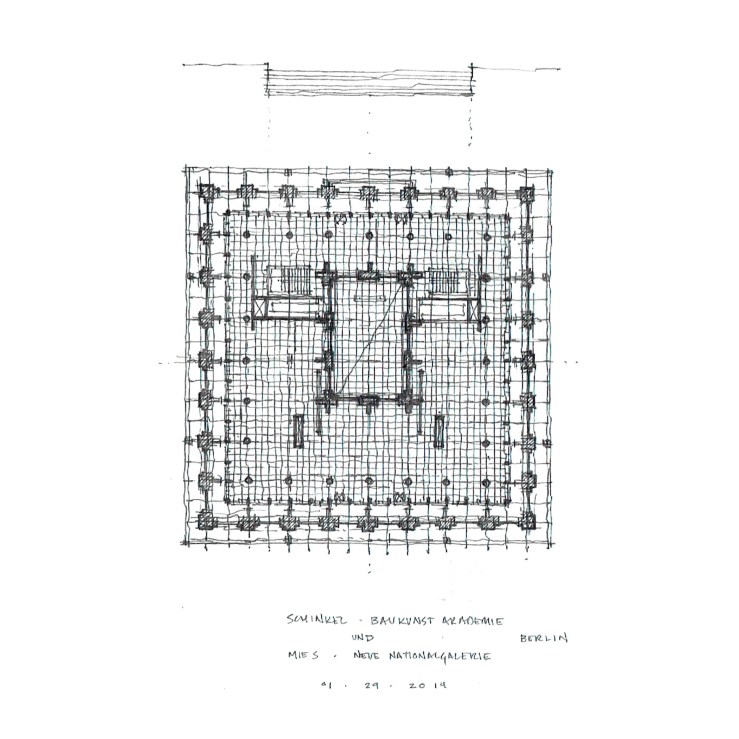

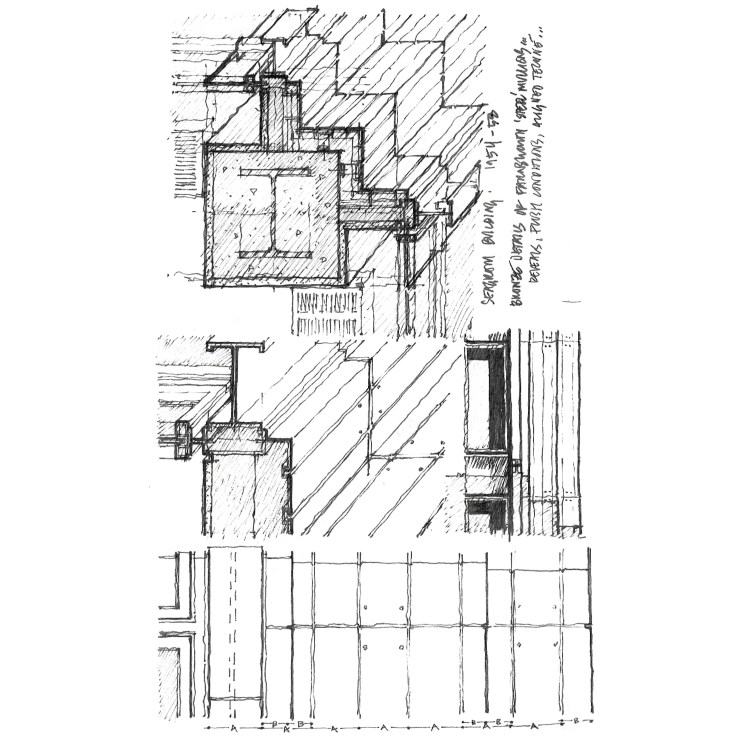

After a short weekend break, I’m back with a few loose ends of Mies that I stumbled on in my sketchbooks. Another take at Seagram (above) and Farnsworth (below), as well as an overlay of Schinkel’s Bauakademie (1836) and Mies’ Neue Nationalgalerie (1968) both square, modular, structures in Berlin.

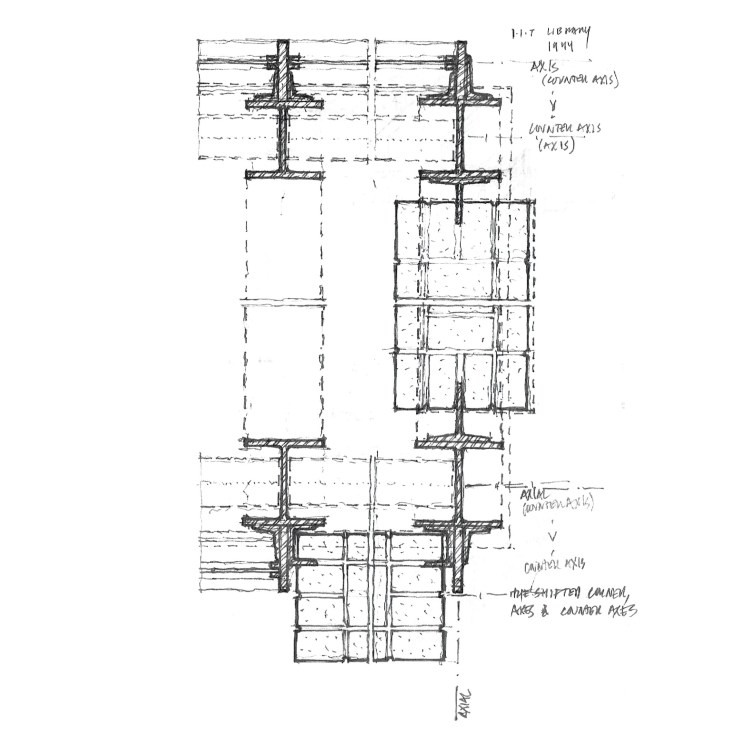

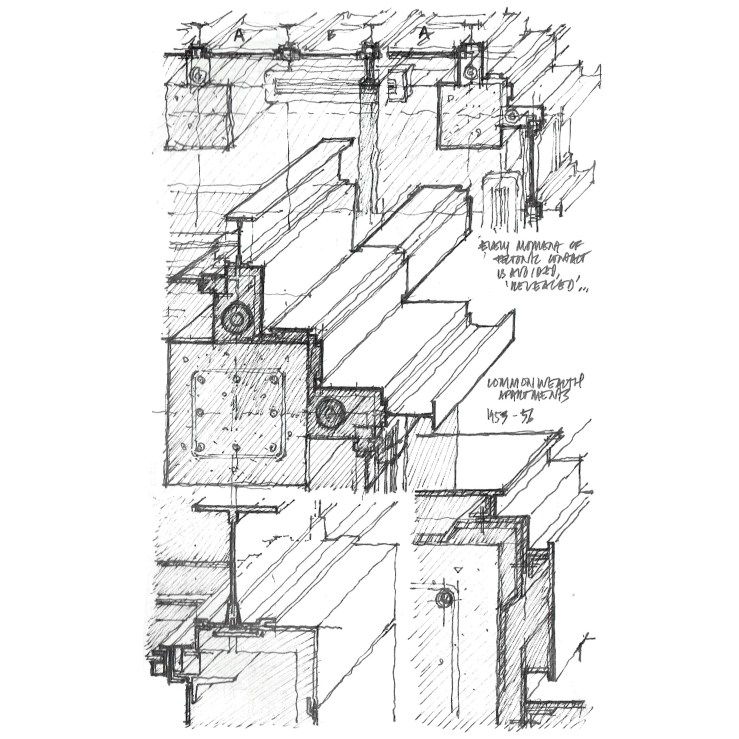

In contrast to yesterday’s post, I’m featuring Mies’ earliest work in the United States (and his first experimentation with the ‘revealed’ corner, where the exterior envelope is set off of the structural grid), classrooms at IIT, for which Mies also completed the masterplan. Here, the frame is still made up of wide flange steel sections, but with buff brick infill panels. The window systems are still solid steel bars welded together – the thermal break found in the aluminum and bronze curtainwall systems was still a long way off.

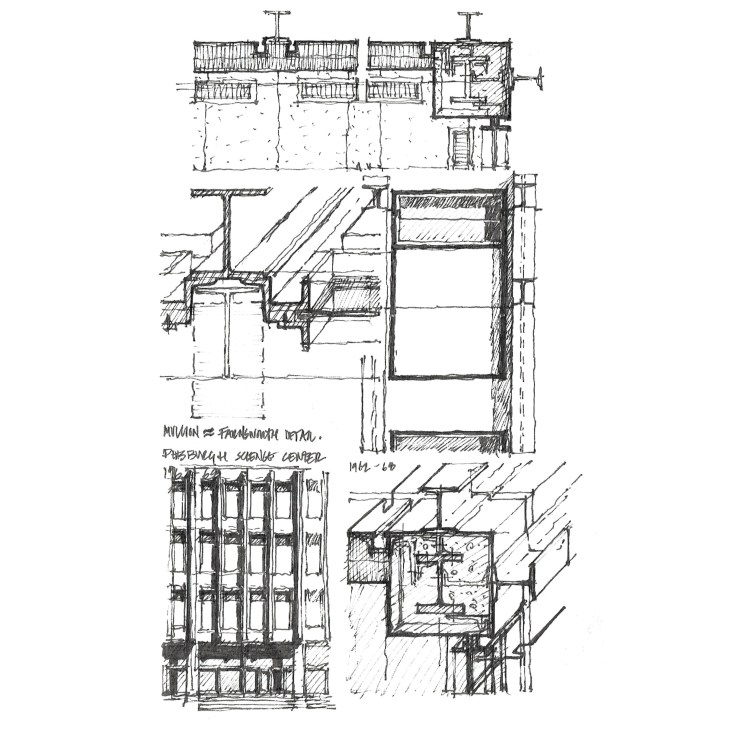

Today, I’m featuring the pinnacle of Mies’ urban tower typologies: the Seagram Building of 1958. The wide flange steel mullions on the Lake Shore Drive apartments are rendered in custom bronze extrusions, with thermal breaks at the windows, but all appearing as though they were constructed of arc-welded steel sections (as at the Farnsworth House). The glass curtainwall is brought proud of the structural column line, allowing the windows to be consistently sized throughout. A contemporaneous example in Toronto follows:

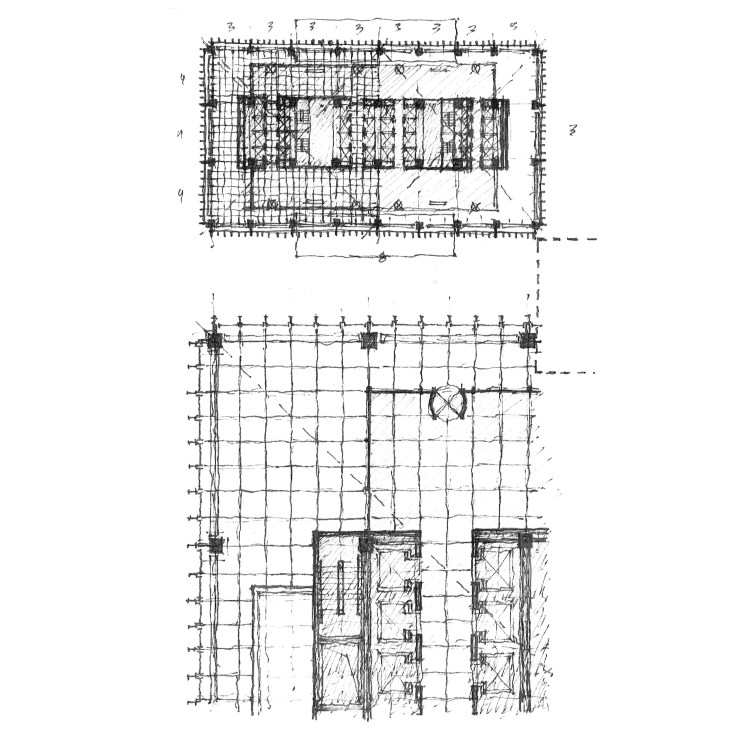

Continuing yesterday’s post, here are yet more of my year-plus studies of Mies van der Rohe’s mature works in details, plans, axonometric, etc.

While working in Chicago, I became painfully aware of how little I actually understood the mature work of Mies van der Rohe, especially with regard to his command of modules, structural regularity, and the finesse of his details. So I drew. I drew every one of his corners I could get my hands on – from the early simplicity of the Lake Shore Drive Apartments to the apex of complexity at the Seagram Building only some 10 years later. Over the next few days I’ll be overwhelming you with these drawings. Enjoy.