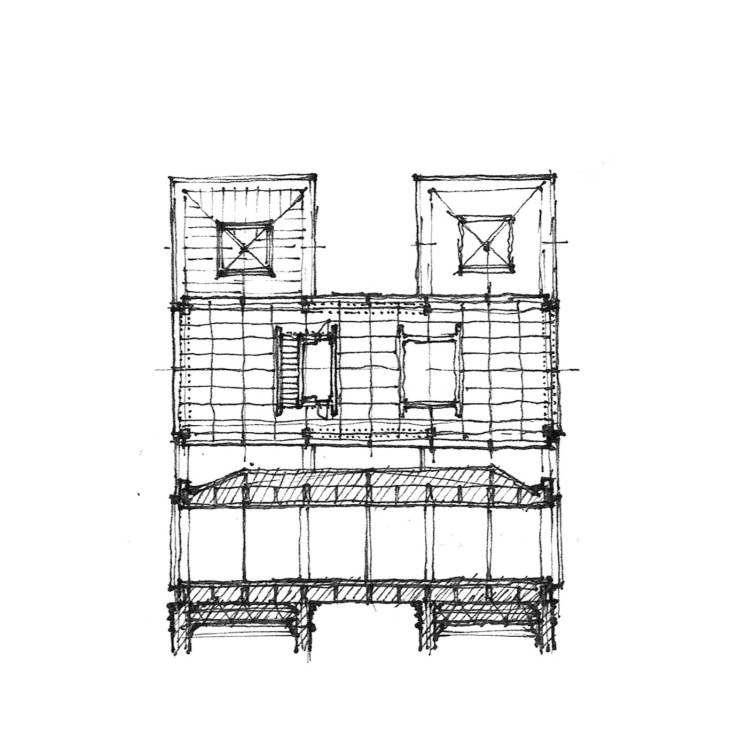

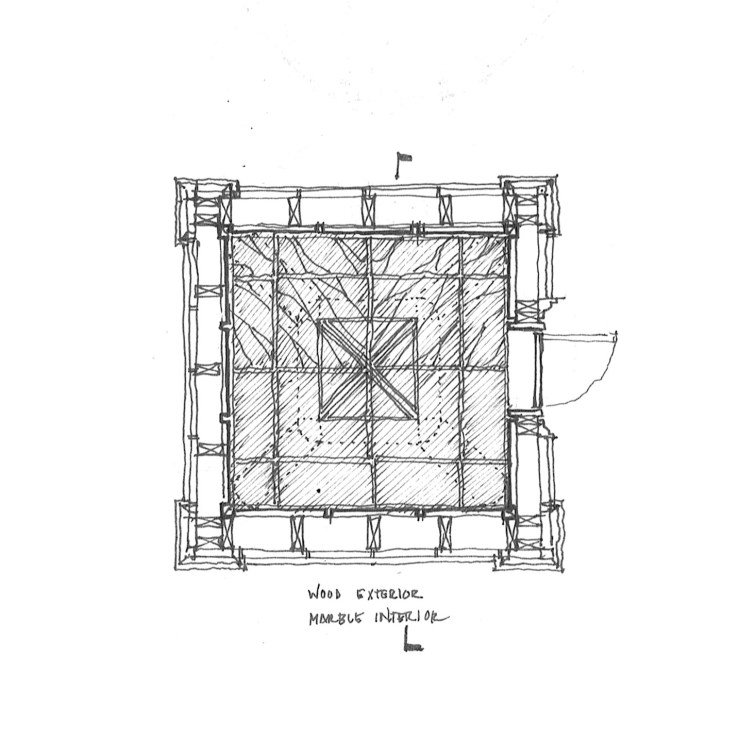

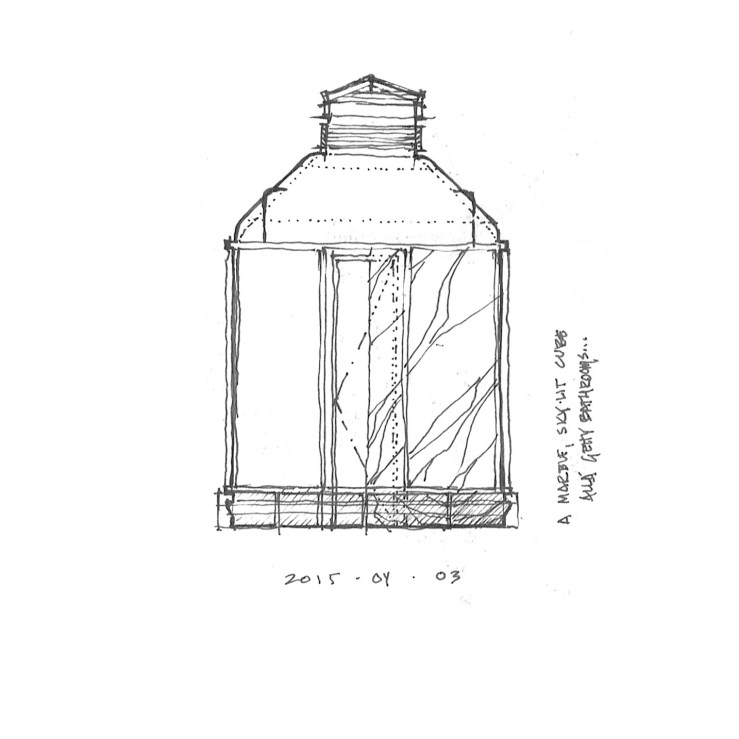

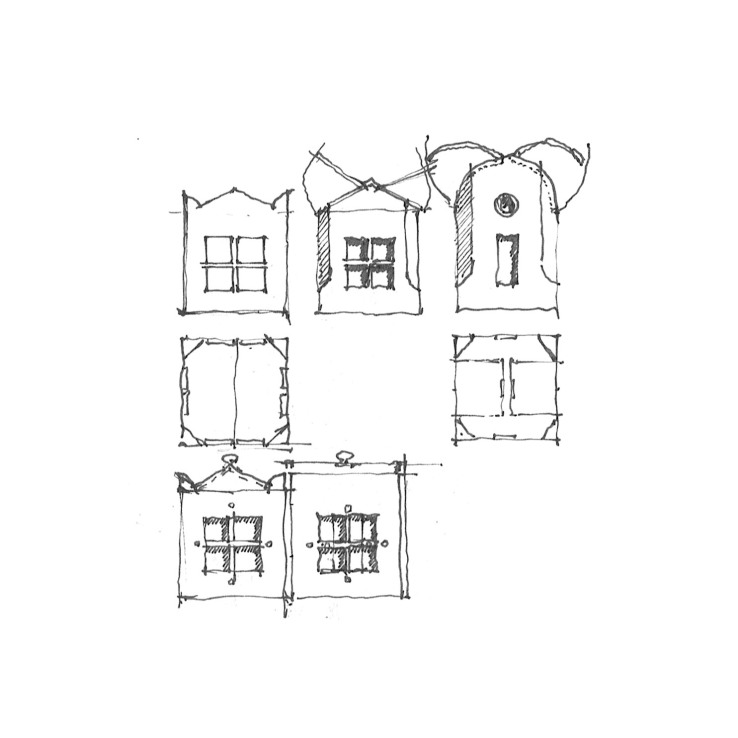

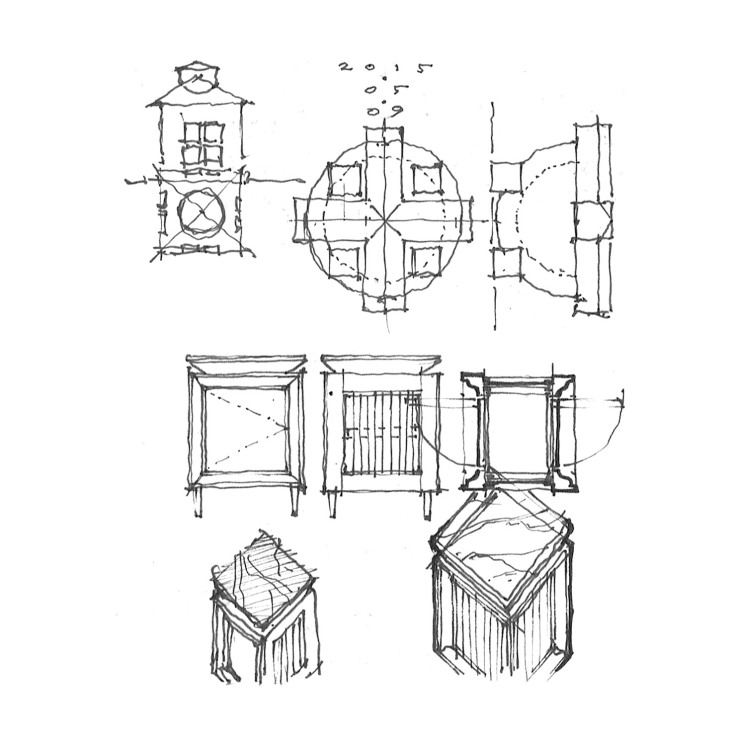

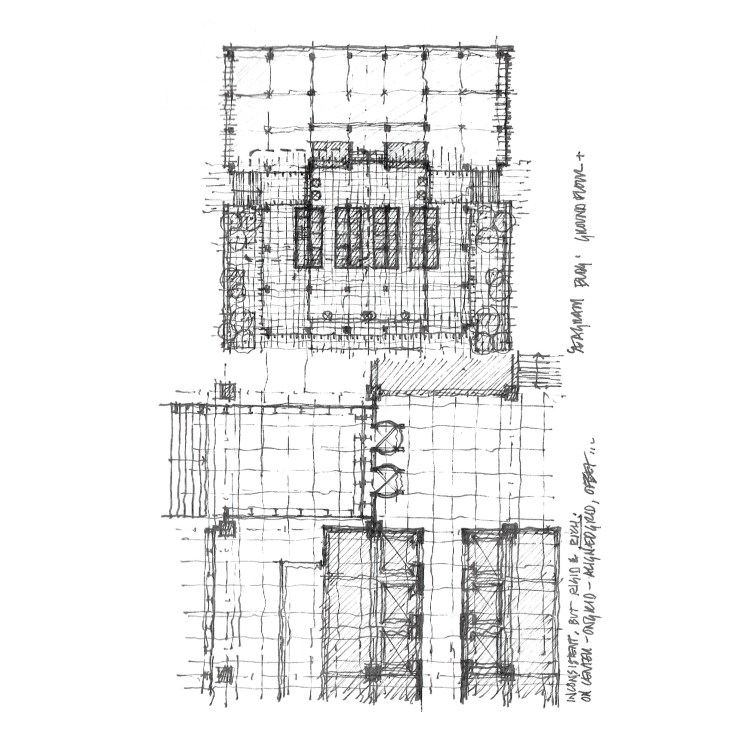

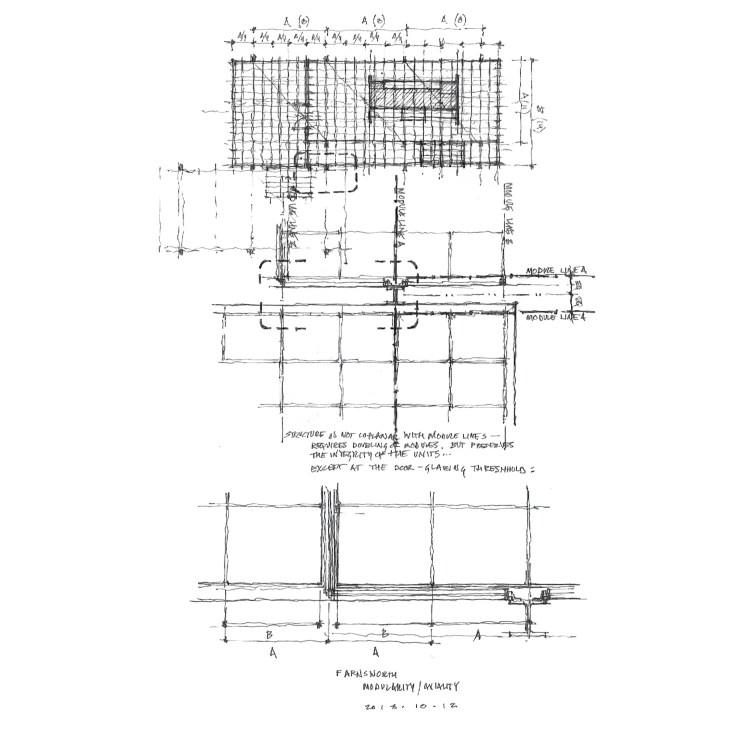

Driving along the coast through Laguna Beach, I noticed a funky little structure now operating as the offices for a small auto repair shop – it was clearly an old gas station, with the concrete pump pads still extant, which I’ve drawn in the top-most drawing. The fascinating bit was that the overall building was a gabled Spanish stucco hut, complete with a red tile roof and chimney, but the service awning was a flat modernist roof, and which cut deep into the gabled volume. The overlap and simultaneity of languages was so simple, irreverent, and playful. So I did my own variation: the plan is the bottom half of the top drawing, the half-elevations are below.